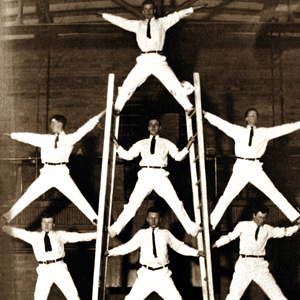

It’s a balancing act...

As lawyers and firms continue to struggle to find the balance between making money, having a life and achieving job satisfaction, new models of law practice are beginning to emerge, both here and internationally. J. Kim Wright recently travelled around Australia to meet with and examine some of our most forward-thinking practitioners and firms.

As lawyers and firms continue to struggle to find the balance between making money, having a life and achieving job satisfaction, new models of law practice are beginning to emerge, both here and internationally. J. Kim Wright recently travelled around Australia to meet with and examine some of our most forward-thinking practitioners and firms.

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

Is it possible for a lawyer to earn a living, make a difference and have a life? New practice models are coming to the fore as pioneering lawyers strive to say yes to this question – to make a difference in the world, earn a good living and have a satisfying personal and professional life.

Grounded in the lessons of the non-adversarial law movement, some of the models and names are familiar and well-established: collaborative law, restorative justice, some types of mediation. Others are newer and less familiar: earth jurisprudence, sharing law and visual contracting. The range of solutions is as broad as the range of problems that lawyers face in their practices and with their clients.

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit Australia. I’ve met hundreds of lawyers who are innovators and must say that I was impressed by the pioneers and innovators I met in Australia. I can only talk about a few of the many inspiring leaders I met, but hope to share a cross-section that informs the reader of their breadth, depth and variety.

One such pioneer is Marguerite Picard, one of the founders of the Melbourne Collaborative Alliance (MCA). As a lawyer for 25 years, she experienced firsthand the ongoing devastation that the traditional divorce process can leave in its wake, including the sometimes irreversible damage to family ties and relationships. Like many lawyers, she went looking for a better way and found collaborative practice (CP). CP is a client-centred approach to divorce and family matters that is becoming increasingly popular in Australia. The International Academy of Collaborative Professionals has 120 members from Australia.

Collaborative practitioners help clients reach amicable settlement after separation, often using an inter-disciplinary team of experts who work together to resolve conflicts. MCA’s other two founders are a financial professional and a therapist.

Changing times

Marguerite is an example of the new breed of integrative lawyers. Integrative law is an international movement that responds to the challenges of law practice with creative, innovative solutions. It blends the human and the analytical. The approach spans personal and systemic change. Integrative lawyers are purpose-oriented, that is, they have a clear sense of their own purpose and the purpose of law. They have a broader view of their roles as lawyers, often seeing themselves as change agents, and they are innovative, looking for ways to serve clients and themselves.

Some of the integrative law models that are court based focus on solving underlying social problems (drugs, homelessness, domestic violence, etc…) and aim to restore the defendant to productive membership in society. These models include disciplines such as restorative justice, therapeutic jurisprudence and problem-solving courts. Programs such as the Melbourne Neighbourhood Justice Centre and Brisbane magistrate Christine Roney’s Special Circumstances Court are just two examples.

The Neighbourhood Justice Centre (NJC) seeks to resolve disputes by addressing underlying causes of harmful behaviour and tackling the issues of social disadvantage. It is focused on local justice and finding lasting solutions that strengthen the City of Yarra. The building is much more than a courtroom. It is welcoming, with colourful art, a volunteer-operated café and meeting spaces for community events.

Magistrate David Fanning is the sole magistrate at the NJC and hears every matter, giving him an in-depth understanding of the variety of justice issues facing Melbourne. The courtroom is small and intimate while maintaining the formality and solemnity of the traditional courtroom, as appropriate to the matters that are heard there. The court is multi-jurisdictional, with a Magistrate’s Court, a Children’s Court (Criminal Division), a Victims of Crime Assistance Tribunal and a Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT). Free legal advice and representation is provided by Victorian Legal Aid and the Fitzroy Legal Aid Service in all matters. The NJC is the only community court of its kind in Australia but there are hundreds around the world.

Community courts are a subset of the larger subdivision of problem-solving courts. There are more than 2500 problem-solving courts in 120 countries. One such court is Brisbane magistrate Christine Roney’s Special Circumstances Court. Like most problem-solving courts, her court works with social workers and partners with service providers, addressing not only the problems that bring clients to court but the underlying issues of homelessness and poverty that have them on the streets. She runs her court with a firm benevolence that provides needed structure, guidance and reinforcement for clients to get their lives on track.

It’s not all about the money

Many of the integrative law models are experiments taking place in small firms. Some are being expressed in Community Legal Services such as TASC (Toowoomba Advocacy and Support Centre), which has a poster in their hallway announcing they are ‘Lawyers with Soul’. Others are taking place at the systemic level. In South Australia, the Smart Justice Report by the thinker-in-residence, Judge Peggy Hora, contained 48 recommendations for justice reform, most aligned with the integrative law movement and many of which have been adopted.

Integrative lawyers often experiment with new business models, seeking freedom from the billable hour and better fee structures for their clients. MCA boasts a flat-fee model, an approach also embraced by Sydney-based Marque Lawyers, who use non-hourly fee structures in business law. Marque was founded by lawyers who had reached the pinnacle of success in mainstream law firms but found something lacking. They decided to create a law firm where they put personal happiness as their motivating goal, relegating maximising personal income to a consequence, rather than a direct goal. Not only do they eschew the billable hour, their office is a physical representation of their tag line of ‘Law, done differently’. A coffee bar is the centrepiece of the office, with glass partitions and interesting seating areas that look like park benches.

Some of the changes in law firms are consumer driven. When a client asked Henry Davis York (HDY) for their sustainability report, they began to explore what sustainability might mean for a law firm. Beyond the environmental issues that are conjured by the term, HDY realised that sustainability policies required them to examine their core values, workplace and relationship with the community, as well as the marketplace. Compared with the general public, lawyers have lower job satisfaction, higher rates of addiction, depression, divorce and just about any other measure of unhappiness. From the lens of sustainability, HDY saw the wisdom of tackling the wellbeing of their staff. They’ve set a goal to be “recognised as a leader in the development and implementation of sustainable business practices in the professional services sector” and are the only law firm I’ve found to actually publish their sustainability reports on the web.

Meditate to mediate

In the past, most legal education did not prepare us to practice holistic approaches. At the core of most integrative law practices is increased self-awareness. Continuing education is provided by consultants like Sandy Wright, a former corporate lawyer from Sydney, who for the past decade has taught hundreds of people from all walks of life how to meditate and manage stress. Sandy has taken her workshops and courses into the boardrooms of some of the biggest companies in Australia, as well as working with companies in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong.

Mindfulness meditation has been shown to have benefits for both health and effectiveness and is becoming a core life skill at places such as Monash University, where there is also a Centre for Court and Justice System Innovation. Innovation is finding its way into other law schools and the new breed of lawyers will be better prepared for the demands of practising law in a new paradigm.

Other law firms seek out the help of consultants who combine law with holistic organisational development tools. In her time practising as a lawyer in commercial dispute, working on complex and protracted litigation, Catherine Davidson came to believe that there had to be a better way to solve disputes. She became a mediator and, later, a consultant in appreciative inquiry, a strength-based approach to both their strategic planning conversations and people development.

Innovative ideas

There are several other models of integrative law that I didn’t see in Australia but I have no doubt that the innovators will soon be adopting them.

Earth jurisprudence recognises that the rights of the natural world and that the good of the whole takes precedence over the parts. It seeks a code of ethical practice as relates to the natural world.

Sharing law recognises the trend towards community cooperation. Shared housing, cooperatively-owned businesses, community-supported agriculture and crowd-funding require a re-evaluation of the arms-length transactions. While often complex, I like to think of this simple example: If you live in a neighbourhood, why do you have to own a ladder if your neighbour already has one, especially if you have a lawnmower you’d be happy to share? If you want to start a neighbourhood tool library, how do you organise it? What about liability? What do you do if the neighbour doesn’t return an expensive tool? How do you afford the tools that you all need but no one owns? Sharing law seeks to answer those questions and more.

Visual contracting is an example of a creative response to the international and multilingual practice of law. Most common in Europe, it uses graphics to make contracts more understandable. In Canada, Rogers Communications v Aliant involved a contract dispute based on one sentence with 45 words, and a comma that a court interpreted as meaning that Aliant could renegotiate the five-year contract after only one year – as opposed to renegotiate with one year’s notice after the end of the five-year term. Resolved based upon English punctuation rules, the French translation held the opposite meaning. In visual contracting, the contract would be diagramed in a flow chart to encourage a clear and shared understanding.

Being an integrative lawyer is about integrating your life and law practice, about aligning your internal and external lives. It is about using your creative problem-solving skills to create a law practice that benefits you, your clients and society.

Since 2008, J. Kim Wright has been travelling the world, exploring innovation and peacemaking in law. Named as one of the American Bar Association’s Legal Rebels, she is managing editor of CuttingEdgeLaw.com and author of Lawyers as Peacemakers: Practicing Holistic, Problem-Solving Law.