A lawyer’s mecca

The perception of a lawyer is often of someone very focused on fees, but since time immemorial, lawyers have been professionally obliged to support the disadvantaged. Stephanie Quine investigates the frustrations and rich rewards of lawyers working pro bono

The perception of a lawyer is often of someone very focused on fees, but since time immemorial, lawyers have been professionally obliged to support the disadvantaged. Stephanie Quine investigates the frustrations and rich rewards of lawyers working pro bono

Rizpah Jarvis once worked as a Commonwealth prosecutor. For Centrelink, she prosecuted mums and students who hadn’t declared their income and were being overpaid, and for the customs department, people who smoked on planes or tried to smuggle birds’ eggs out of Australia, “somewhere down their underpants to keep warm”.

“If you’re a prosecutor you can present the facts or you can be a bit of a bulldog. I just presented the facts,” says Jarvis.

Despite some defendants calling her a “hoity-toity lawyer” with no knowledge of hardship, Jarvis harboured a heart for the disadvantaged.

After several years working as the legal and compliance manager for a property investment group, and then in Mills Oakley’s building and construction group, Jarvis joined the humanitarian team at Salvos Legal.

For just over a year now she has helped people who can’t afford a lawyer win protection visas, regain custody of their children, avoid drug and alcohol charges and begin rehabilitation and counselling for mental health issues, rather than go to jail.

Her expertise, along with that of around seven other solicitors in the firm’s Surry Hills head office, is offered on a pro-bono basis.

Funding humanitarian-lawyer salaries through its commercial arm, Salvos Legal is a self-sustaining practice which offers free legal advice and full-time representation in courts and tribunals in criminal law, family and children’s law, debt, housing, employment, and migration and refugee law.

But that’s not all.

“I’ve got a couple of guys I’m helping who are doing the Salvation Army rehab program,” says Jarvis.

Some call it wrap-around servicing; some call it holistic servicing. Jarvis knows that, usually, a disadvantaged clients’ legal issue is one of a whole host of others and tries to engage clients with the full range of services they need, such as Salvos’ crisis accommodation, financial counselling or employment assistance.

But it’s not always easy to represent – let alone communicate – with disadvantaged clients.

Rizpah Jarvis, Salvos Legal

“You have to be very patient and very flexible. You don’t get clear and concise instructions like you would with a commercial client who will get you things when you need them, and be clear about what they want,” says Jarvis. “Usually our clients don’t know what they want or they don’t know how to ask for it.”

Jeremy Rea is a criminal lawyer and solicitor advocate with the Homeless Persons’ Legal Service (HPLS) – a pro-bono initiative set up by the Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) in 2004.

After 20 years in private practice, Rea now mainly defends the “street offences” of homeless people in the local and district courts, free of charge.

From setting a meeting time, to deciding whether to put his client in the witness box, Rea is constantly mindful that “homeless people are homeless because they cannot cope with mainstream society”, and that drug or alcohol problems limit their ability to look after their own affairs.

“My clients tend to have a fairly flexible view of time and days and that comes from the fact that they are often unemployed [and] each day melds into another,” says Rea.

The joys and frustrations

Rea relishes the challenge of pro-bono work and says that, despite the frustration, he enjoys his clients and representing them.

“It’s never boring ... Everything’s out of the left field, even the most simple of cases. I could have a simple, minute [marijuana] possession charge and think, ‘Oh, that looks good’, [and then] you see the client’s record and they’re on a suspended sentence or a good behaviour bond, so it changes the whole complexity of the case,” he says.

Jarvis describes pro-bono work as “the lawyer’s mecca” because it offers the chance for lawyers to use all their legal skills and experience to make a big difference.

“Resolving a matter for a commercial client is usually something tiny in the scale of their business, whereas when you’re working pro bono, being able to fix that one little thing can make the biggest difference and have the biggest effect on their life. That’s pretty rewarding,” she says.

Rea recalls how past clients have become upset on the stand or “become irate and started gesticulating” while he is cross-examining police or a victim. He says he takes them outside, calms them down and tries to explain the situation.

“Anxiety, stress – all those things that occur on the streets just build up within them when a case is in court and it becomes very hard,” he says. “But it’s also one of the great things about it because it gets you to recognise the importance of those factors in running any criminal case.”

Seeing a need

To Australia’s great shame, says the CEO of PIAC Ed Santow, 100,000 Australians are homeless each night.

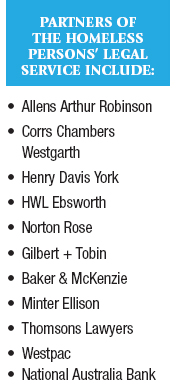

Without the assistance of lawyers within both private practice and in-house, pro bono projects like the HPLS would not have the manpower or expertise needed to assist so many homeless, vulnerable Australians.

Last year 350 lawyers working in commercial firms, legal aid and in-house provided regular legal advice and assistance through the HPLS.

“That’s $1.5 million-worth of free legal advice and assistance provided from the commercial sector,” says Santow.

Following a legislative amendment to the Legal Profession Act 2004 this month, Victoria’s 2,700 in-house lawyers can now also undertake pro bono work. Previously, practising certificates available to Victoria’s in-house lawyers limited them to providing legal advice to their employer only.

John Corker, director of the National Pro Bono Resource Centre (NPBRC), says now is the “prime opportunity” to re-promote pro bono work and for organisations to get involved [and] give back to the community.

While the head of Westpac Group’s institutional bank legal team, James Hutchinson, welcomes the amendment in Victoria, he says the state-by-state approach to pro bono practice – and professional indemnity (PI) insurance – still hinders Westpac’s interstate members who are keen to do pro bono work.

“We had the advantage of using New South Wales as a testing ground for our initiatives, but it’s a pity that there is [still] not a uniform, national position on the ability of lawyers to participate in pro bono,” says Hutchinson, who coordinates the pro bono work undertaken by Westpac’s team of over 28 lawyers.

Although there is a well established commitment to developing pro bono programs in private practice, Hutchinson says that in an in-house environment, pro bono work, to date, has largely been a case of in-house lawyers taking activities “on their own back”.

“At Westpac we had executive support for [pro bono activities] and we have a well-developed corporate social responsibility program,” he says. “Both of those are really important for an organisation that is trying to get a pro bono project off the ground.”

A number of pro bono projects undertaken by members of the legal profession often involve cooperation between different law firms, providing variety of work for pro bono lawyers.

In 2009, the NPBRC launched a scheme which provides free PI insurance for any pro bono project that corporate lawyers wish to undertake. Through the PI cover provided by the NPBRC, Westpac lawyers use their knowledge of corporate governance and structural issues for organisations to provide direct support to various not-for-profit organisations.

Through the HPLS and Mathew Talbot Hostel, Hutchinson and his team have had the opportunity to “buddy-up” with Gilbert + Tobin lawyers and advise homeless people on issues that aren’t so closely aligned with their usual work.

Hutchinson recalls a member of his team helping a homeless man re-establish his identity through the HPLS after he was mistakenly declared dead, having been “off the radar” for seven years.

“Lawyers have a great passion for deploying their legal skills and showing their wares very widely, not just in a work environment,” says Hutchinson. “This sort of work is a great opportunity to do that and to get skills in dealing with people who have unusual issues.”