Under a suite of new changes that includes consequences for non-compliance, strict limits on cross-examinations and affidavits, and a number of new appointments, the Family and Federal Circuit Court merger promises to deliver justice more effectively, efficiently and inexpensively, Chief Justice Will Alstergren has told the profession.

The newly merged Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (FCFCOA) will start operating under updated rules from 1 September with the aim of delivering cost-effective and efficient judgment within 12 months of filing an application. The changes include a single point of entry, harmonised forms and updated processes.

“The courts have been working diligently to build a court system that is innovative, focuses on safety of children and litigants, and changes the culture of family law,” the Chief Justice said. “The courts will bring efficient and effective delivery of justice, common processes to simplify our court program and will make it a much more cost-effective system for all litigants. It is a system that Australian families finally deserve.”

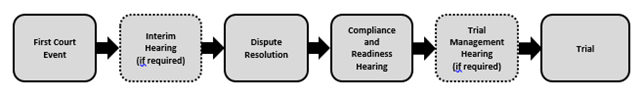

Aiming to achieve a “substantial improvement” of resolving up to 90 per cent of matters within 12 months, the new court will follow a nationally consistent case pathway (pictured below), with the first court event set to take place within six to eight weeks of filing. From there, parties will enter mediation or dispute resolution before the six-month mark and, if they are unable to settle, will proceed to trial.

“Our aim is to get cases through our pathway and have disposed of as much as 90 per cent of it within the 12-month period. The courts have been gathering evidence on a weekly basis, and more information will be circulated on this over the coming weeks and continually over the coming months as new arrangements are implemented,” the Chief Justice said.

If there is a “high risk or real assurance” of urgency in particular matters, Chief Justice Alstergren said that the courts can accommodate holding the first court event and the interim hearing on the same day, speeding up the entire court process. Any matter already listed may also be moved forward under new available dates.

Under the single point of entry, applications will be filed in division 2, providing an “opportunity to assess and triage all matters at the point of filing”. This will occur at the very outset of the proceedings and will draw from existing practices that currently exist around child abuse, family violence and parenting risk matters.

One set of forms will also be “finally” used across both divisions, again similar with the notices in child abuse, family violence and risk that was harmonised last year. The harmonised rules have received extensive consultation from the profession and other stakeholders and are currently being settled into a formal instrument. Essential practice directions around case management have also been circulated to each state’s major bar association, law society, legal aid and commissions.

“Through this structural framework, the court is aiming to achieve a worldly, best-practice family law system and a court that is truly national, with consistency nationally. We have modernised the court using the work we have done electronically [over COVID] to create a system that responds to the increasing prevalence of risk to children and vulnerable parties,” the Chief Justice said.

In an effort to focus parties on timely, final resolution of their disputes, the new rules have imposed limits on the lengths of affidavits. From September, up to 10 pages will be permitted in division 2 and 21 pages in division 1. The rule also ensures that interim hearings are kept under the two-hour mark and cross-examinations are only allowed to move ahead under extremely limited circumstances.

New consequences will come into play for parties and litigants who fail to follow the rules or unnecessarily add time to the matter. If there is no reasonable excuse, “they will be dealt with very quickly” and orders may be reassessed. Chief Justice Alstergren said there will be a lot more focus on ensuring orders are complied with.

“Compliance in family law has long been a real problem for our system. It is perhaps the worst jurisdiction in Australia for compliance, and it’s not just unrepresented litigants that don’t comply. Time and again, we find a lack of compliance interferes with the effectiveness of the new court, but also the confidence that people have in our justice system. Compliance will be a real focus going forward,” he said.

Similarly, if a client takes the view or advocates a view through their representative that they have no disclosure and may be required to provide an affidavit to attest to that — adding more time to the matter — the Chief Justice said there could be consequences: “We can’t have matters that go on forever. They will be required to file an undertaking, and if they breach that, there will be certain consequences.”

Division 1 will retain jurisdictions to hear family law appeals where needed, but there will not be a separate division for these matters. All division 1 judges will be able to hear appeals either as a single judge or as part of a full court. Appeals in division 2 and family law magistrates of Western Australia decisions will be heard by a single judge unless the Chief Justice considers it appropriate to order a full court.

President Juliana Warner said the new rule changes follow inquiries by both the Coalition and Labor governments, “which have shown in recent years Australia’s family courts have struggled with high caseloads and limited resources”. However, she said it is not surprising that given the high stakes involved in the extent of the reforms — and how it will play out over the next few years — there has been some public debate.

Some of the more common concerns include that it will increase costs, delay and stress for families if the lack of resources goes unanswered. Responding to concerns that the merger will mean diminishing specialisation, Chief Justice Alstergren said it was “hot air”, “unfounded” and that “nothing could be further from the truth”.

“We have been very forceful on the government on this and there are sections [in the new rules] that require specialist knowledge in any appointment of judges, including handling both high-level domestic cases and family law violence,” he said.

“You only have to look at the level and competence of the people who are being appointed to the court. Look at the number of silks that have been appointed to see the kind of depth of knowledge, skill, ability and aptitude we have. People should not be under any apprehension that the level of skill is decreasing and not growing.”

As for resourcing, the Chief Justice said the federal government has provided more than $100 million in new funding which has assisted an “intensive recruitment drive”. The new court will have 111 judges, including 90 specialist family law judges. A number of new registrars are also expected to be added over the next month.

Existing and new registrars will receive a name change to “reflect the nature of the work that they have been, and will be, doing”. From September, senior registrars are to be referred to as senior judicial registrars, registrars will be judicial registrars and assistant registrars will have the new name of deputy registrars.

Also getting a new name and new responsibilities are expert child psychologists, now known as court child experts. Before the dispute resolution stage and if input is necessary, the court child experts may create a new report — known as the child impact report — that will give a voice to children “at the earliest stage”. This report may be used in interim hearings and potentially as evidence in trials.

“We are appreciative of the co-operation we have been getting from the profession,” Chief Justice Alstergren concluded.