We are currently seeing an increase in expectation and momentum of regulatory co-designs across the legal profession, as the model supports broader sustainability, inclusive and social awareness principles that are rapidly becoming the benchmark, writes Dr Rob Nicholls, in collaboration with Unisearch.

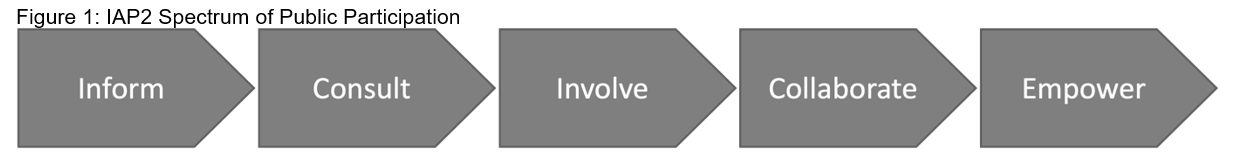

On 16 February 2022, Jane Halton argued that co-design, not secondments, is the key to enhancing the public services’ understanding of business. Increasingly, there is an expectation that regulatory processes use stakeholder’s participation, including customers, in the development of their products, prices, and regulatory settings. The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) has a spectrum of participatory co-design:

Engaging stakeholders in aspects of design has a long history in technology but is a recent feature of regulated sectors and public decision making. The rise of bodies such as the IAP2 reflects the extent to which retail consumers and other stakeholders are important players in co-design. For instance, globally, the tariffs under which customers purchase energy are co-designed by representatives of those customers in the energy sector. In this environment, regulators have a high level of concern to ensure that co-design was participative. That is, the regulator examines what was tried, what was heard, and what was applied.

The IAP2 spectrum has associated promises to the public ranging from “We will keep you informed” to “We will implement what you decide”. This last promise provides an insight into how deeply co-design can drive a business or government department. For example, the Australian Energy Regulator says, in the context of five-year pricing proposals: “Issues over which consumers will have more influence should be at the upper (empower) end of the IAP2 spectrum … businesses should encourage consumers to test assumptions and processes that underpin the proposal. Where consumers aren’t well equipped to do so, this may entail providing them with additional resources and supporting them to commission independent analysis.”

Governments at Commonwealth, state and local levels are increasingly expected to use participatory processes in the co-design of solutions. For instance, the City of Parramatta sets out which decisions fall wherein the spectrum (with “involve” as the highest). The NSW Department of Industry does the same with respect to water.

Suffice to say that there’s an increase in expectation and momentum of regulatory co-designs throughout the industry, as the model supports broader sustainability, inclusive and social awareness principles that are rapidly becoming the benchmark.

This raises a series of challenges for legal advisers.

Where does the lawyer fit into the calculation if stakeholders are designing prices and products? In providing advice to clients, whether from government or regulated businesses, it is important to understand how the process works and the role of each stakeholder and stakeholder group. There are many players in a deliberative process. These include stakeholders ranging from customers to representatives of disadvantaged groups, engagement consultants, communications consultants, and the clients themselves.

Just as important as the lawyer’s role is whether these other consultants are replacing the traditional role of lawyers as advisors. To some extent, the answer to this question is “not yet”. However, this does not mean that there is no risk of scope creep from other consultants.

That said, being on the front foot of regulatory co-design can be advantageous. Co-design is already required in some regulated sectors ranging from energy to medicine. It also makes sense in areas as diverse as finance and telecommunications. For example, ensuring that a financial product meets both regulated design and distribution obligations and consumer needs could be achieved by the use of co-design. Advice that this is an option is likely to be highly valued.

In addition, co-design has the potential to foreclose regulatory intervention. Compelling evidence of the effective use of regulatory co-design provides a strong rationale that regulatory intervention is not needed and may be disadvantageous to stakeholders.

There are already several consumer advocacy groups and engagement facilitators active in the regulatory co-design space. There is a role for lawyers, both in-practice or in-house, to be part of the regulatory co-design sector. It’s an area where the “big four” accountancy firms have not yet made a mark and one where the legal profession could establish and maintain a presence. However, it requires a different mindset from the usual interactions in the regulatory space.

When considering the impact of regulatory co-design, we make the following suggestions to legal professionals: