Whether you believe the 2017 same-sex marriage postal survey was a showcase of democracy at its best, or an abdication of responsibility by our elected officials, it did serve to offer a layer of closure to a debate that had raged across Australia for years.

And while there was a plethora of sociocultural and political takeaways from that process, both positive and negative, the question of corporate social responsibility on the question of such issues was one that loomed particularly large, with some cheering the support offered to the “Yes” campaign by national giants like Qantas, and others – including numerous parliamentarians – disapproving of such advocacy.

But what is perhaps more pertinent is the action being taken on the ground within those firms; how and what institutions and individuals in law are doing to address the myriad issues faced by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex persons, and those other sexual orientations, within the Australian legal profession.

Such an examination is necessary, regardless of legislative progress. Lawyers Weekly, in partnership with Thomson Reuters, spoke with a handful of legal professionals, including former Justice of the High Court of Australia, the Hon. Michael Kirby, about the current state of affairs with regards to diversity and inclusion for LGBTQI persons in law.

Reflecting on years gone by

Retired judge Mr Kirby remarks on the differences now compared to when he was coming through the ranks of the legal profession. The world was incredibly different for him growing up, he says, and it was one in which he felt very alone.

“I can’t say I [experienced] a lot of homophobia, because I was always in positions where it really wasn’t discussed, and it was all kept very silent,” he reflects.

“But I did feel myself the subject of a deal that was done in society, and the deal was, ‘do not mention it’. Do not ever mention this issue. You keep quiet, and be ashamed of yourself, and we will also keep quiet and leave you alone. That was the deal.”

The legal profession is unique in its capacity to make meaningful, social change, he notes, and is therefore charged with responsibility to lead by way of amendments to Australian legislation, new conversations on LGBTQI rights under the law, and continuing the process of providing new information about the issues to legal professionals so that they may be able to subsequently serve the community around them.

“I was really made to feel like I was second-class, and I have a sense of unhappiness about that happening in my country. You like to think of your country as [one] of justice and fairness,” he says.

“The law can be a guardian and a protector, and not an oppressor, which is certainly was when I was growing up.”

The Australian legislative process has taken steps over the past few months to address some of those oppressive constraints, namely the ability to wed. But while some see the postal survey process as the end of the line for such sociopolitical discourse, many others still see a long road ahead.

It’s because of this that Mr Kirby and his partner of 49 years, Johan, are still considering whether or not to get married, even though it is now legal for them to do so.

“Obstacles were put in our way that had never been before put in the way of progress in Australia, and people were saying nasty, unscientific things,” he recounts.

“We won’t be happy until there is true equality, and equality in our hearts and minds.”

How the profession is taking action

Mr Kirby submits that “for a company which is involved in communications globally, and is involved in law and justice, it is a natural thing that it should be concerned about LGBTQI rights”. For Thomson Reuters and Allens, such concern is evident.

Thomson Reuters has multiple avenues through which it looks to improve the LGBTQI experience: its Change Makers Program aims to bring together its key business leaders to commit to and take action on improvements to diversity and inclusion across professional services organisations with whom it collaborates, and its Pride at Work Network looks to create safe and inclusive workplaces and realign business objectives with idiosyncratic diversity needs.

In addition, the tech, information and publishing provider boasts a partnership with Stonewall Global Workplace Briefings, which provides practical guidance for LGBTQI employees through legal, cultural and workplace best practice information.

The latter initiative has been especially meaningful for Thomson Reuters Pride at Work co-chair Tim Pollard, who grew up in what he described as an “extended rainbow family”.

“I experienced homophobia as a young child at school and in my early workplaces. So it’s incredibly important for me, as a member of the LGBTQI community, to work at Thomson Reuters: a place that prioritises, promotes and really strives for diversity and inclusion in the workplace,” he says.

Pride at Work also allows Thomson Reuters to better engage its customers, he notes, as the organisation can tailor its products to meet the needs of customers who are concerned with LGBTQI initiatives and issues.

His fellow co-chair, Shelly Mulhern, highlights how important such actions are, particularly at a time when there is a need for more visible role models in this space.

“[Emerging leaders] must have the courage to get up and be those leaders, be visible and take it upon themselves to be those roles models to younger people,” she says.

“For me growing up, it would have been great to identify with somebody, another gay woman, who was in a leadership or senior role. Just have the courage to get out there and do it.”

Being proactive on this individual level – as well as immersing herself in organisation-wide activities – has allowed Ms Mulhern to feel “completely comfortable at work” and kept her motivated coming in to the office every day.

“From personal experience, being able to be my authentic self and talk about my weekend, my partner, my social life made me feel comfortable. You’re going to keep coming to that place if you feel that way,” she explains.

Allens is another example of a player in the profession which is taking charge on the diversity and inclusion front.

Competition partner Robert Walker champions the firm’s LGBTQI Network, which includes allies, and acts in conjunction with the firm’s existing formal policies to ensure and reflect a culture of inclusiveness and diversity.

“People at Allens know there is not just formal support, they know there are people to speak to if they have any issues so they can genuinely feel on the ground, at the coalface, that the firm is committed to ensuring a diverse and inclusive work place,” he says.

Such practical support was paramount, he says, during the postal survey period in 2017, which proved “quite difficult” for some people at the firm. Having both the formal and informal structures in place, he argues, helped bring people closer together.

“Having that network – which has been around since 2011 – enabled us to formally and informally make sure that people felt supported during the debates and the postal survey,” he says.

“Allens was the first firm to publicly come out in support of marriage equality, long before the postal survey, but when the debates were initially being had, so we definitely took a role in ensuring staff felt the support the firm had for them.”

The firm’s Network, as stated on its website, provides opportunities for members to build relationships, network and provide pro bono assistance on matters of interest to the LGBTQI community.

The Thomson Reuters Pride at Work co-chairs also argue, for firms considering greater pushes on LGBTQI issues, that diversity and inclusion initiatives are both good for business and for employee engagement.

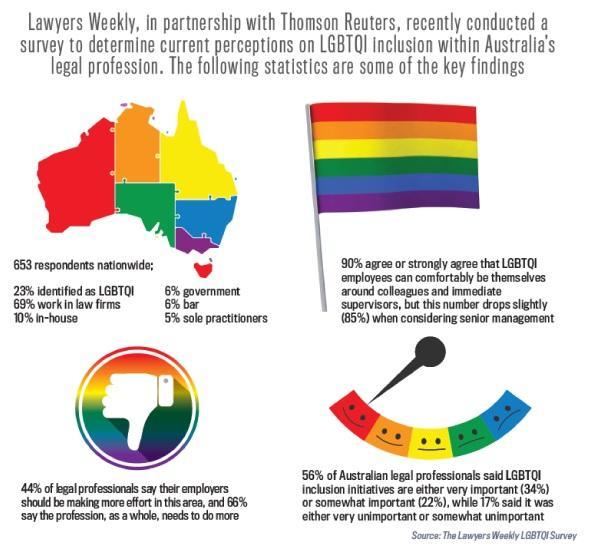

“Our recent survey [with Lawyers Weekly] found that there was an 11 per cent staff retention dividend when there were diversity and inclusion policies, and [advocacy] groups, within an employer,” Mr Pollard says.

“It’s good for team productivity and morale, [with a] possible increase of 30 per cent for workers in [workplaces] where there is diversity, inclusion and product work.”

Firms should also appreciate how difficult it can sometimes be to attract and retain good talent, according to Mr Pollard.

“The last thing you want to do is block out people from your organisation. You want to be as diverse as possible, and attract creative, innovative people into your organisation,” he says.

An honest approach

Mr Kirby lauds the efforts by businesses such as Thomson Reuters and Allens, noting how far the profession – and, indeed, wider society – has come since his early days.

But the former judge says that while there were indeed a multitude of benefits for firms in the pursuit of justice, equality shouldn’t have to be incentivised and promoted in the ways it currently is across the board.

“We really shouldn’t have to justify this – there has always been a LGBTQI cohort in the population, and we shouldn’t have to say there is a dividend through which you’ll make lots more money and it’s good for shareholders. This is the right thing to do,” he says.

“It’s good for business, but it’s also good for being truthful, honest and modern.”

Any institutional initiative must, Mr Kirby espouses, have consideration for a reconciliation of fundamental human rights, in the same way, he notes, the free exercise of one’s religious beliefs is a fundamental right.

“There’s a principle that one human right has to bend if, with the swinging of your arm, you swing until you hit me on the nose,” Mr Kirby explains.

“And, therefore, when you hit a person on the nose with your religious freedom, that’s where your religious freedom has finished and you had to adapt just as gay people have to adapt to a society which is overwhelmingly non-gay, or straight.”

The former judge fears there will be “nasty” debates about such freedoms in the future, with those who wish to re-litigate the question of same-sex marriage coming back out of the woodwork to try to “wind back the equality” of LGBTQI people.

“That’s not going to happen. The people are going to stand up against that,” he predicts.

Advocacy

On the ground, many are not waiting around for positive change from their workplaces and are instead searching for individual initiatives that address their various idiosyncratic needs and desires.

One shining example is Out for Australia, a not-for-profit which addresses LGTBQI issues for students and young working professionals across industries, including law. Launched in late 2013 as Out for Sydney, the now-nationwide advocacy group aims to provide visible role models, mentors and content for up and coming LGBTQI persons and strengthen community ties.

Chief executive Luke Furness, who is also a Brisbane-based tax lawyer at Clayton Utz, says that the group’s mentoring program and networking and speaker events offer individuals proactive opportunities to seek and garner the sociocultural support they may need for personal development and growth, as well as in navigating the professional landscape and any ingrained hurdles that may be present.

“Even back in 2013 [when Out for Australia was founded], initiatives for sexual diversity were really patchy. There was a lot of work to do in terms of making young people (really, those of all ages) feel safe, comfortable and free to be themselves at work,” he says.

“The goal now remains to make all LGBTQI people feel safe and comfortable in the workplace, even in organisations that celebrate diversity.”Mr Walker recognises the importance place that advocacy groups such as Out for Australia have in the larger conversation, and notes Allens’ informal support for their initiatives. Networking opportunities – whether internal or external – are important for relationships and community, he says.

“[They give] our people, and our clients, a chance to meet, socialise and network with other LGBTQI professional members of the community and allies to build their formal and informal networks,” he adds.

Perceptions of existing initiatives

While steps are being taken toward increased diversity and inclusion, both at institutional and grassroots levels, there has emerged a growing disparity in perception between achievements made and substantive change, with – as the nationwide survey revealed – varying impressions between the LGBTQI and non-LGBTQI legal communities of the success of such achievements.

This “gap”, as Mr Furness puts it, has been there for as long as he has been involved in diversity inclusion advocacy work.

“It certainly accords with my personal experience that allied or non-LGBTQI people have an expectation of how diverse and inclusive the environment is, and that doesn’t always accord with the on-the-ground reality,” he explains.“

In most cases, there is a danger that leaders will make decisions or assumptions with regards to diversity that might be a little rosier than how progress is actually being made at the coalface.”He notes, however, that from his experience there is still hope to be drawn from the disparity, as those firm leaders are more often than not genuinely sincere in their efforts.

What is needed, he surmises, is greater transparency about perceptions made between parties so that progress can proceed more effectively.

Mr Walker supported this, saying that listening to your staff about their experiences is the best way to address the perception gap.

“That’s why having networks, like we have at Allens, plays such an important role, so that when people at whatever level of seniority do feel like something needs to be done, they’ve got channels to do so,” he said.

This transparency and openness must coincide with more progress, however, as even positive outcomes have negative impacts, as the postal survey taught us, Mr Kirby argues.

“People said [the survey result was] a wonderful outcome, and in one sense it was a silver lining to a very bad process. But almost 40 per cent [voted against it], and that isn’t so wonderful,” he says.

“Therefore, we’ve all got to work at trying to make Australia a better, more inclusive, just and kinder place, and I think the journey’s just begun.”

Ms Mulhern agrees, saying the survey process “was quite impactful”.

“It’s great moving forward, it’s fantastic, but it was very slow to come, almost a little embarrassing to be honest,” she offers.

Appreciating how much work is still to be done, both within the legal profession and outside of it, starts with acknowledging that “40 per cent of our fellow citizens were against them, denigrated and disrespected them”, Mr Kirby submits, is but another step on the way to closing the perceptions gap.

Experience of transgender persons

Mr Kirby also argues, as part of this larger conversation, that the specific needs of particular persons are taken into account, rather than simply painting the entire LGBTQI community with one broad brush.

The needs of trans persons, for example, are pertinent moving forward.

“You’ve got to reach out within the LGBTQI community to give emphasis and recognition to trans people,” he says.

“They are often ignored in this debate. How many trans employees are there that we know of, do we understand their story, are we empathetic, and, are gay people empathetic to that?”

Mr Furness agrees that this is an area demanding increased focus.

“We have made leaps and strides in terms of improvements for gay men, but I think there’s work to be done for lesbian, bisexual and trans women, and people of ethnic and cultural backgrounds,” he says.

“But we also need to be thinking about people that are not even in the legal market for reasons of their LGBTQI orientations, such as trans people. We don’t have a lot of trans representation in law, because the experience – as a generalisation – is such that it’s difficult to get into a firm or enter the legal market.”

“We need to think about how we can make sure we promote inclusivity with trans people,” he says.

Mr Walker also acknowledges that, across the profession, this needs to be taken more seriously.

“We recognised this a few years ago and took the initiative to make sure that we have, firstly, policies in place for transgender people to support them through transitioning such as through leave and other support for those processes,” he says.

It was also important for the firm to understand the language around topics pertaining to transgender persons, he notes, and thus the firm received training from Pride in Diversity on the importance of gender neutral pronouns and other matters pertinent to those going through transition.

“In reality, not everyone knows people going through, or have been through, that process, or are transgender or intersex-identifying people,” he advises.

As such, practical steps should be taken to ensure that firms have the rights structures in place, he argues.

Tokenism and optimism

Another area identified for improvement coming out of the Lawyers Weekly/Thomson Reuters survey was the need for initiatives to move beyond tokenism. While over half of surveyed legal professionals think their employers’ efforts are substantive, 15 per cent think their workplaces only make a token effort, and 30 per cent were neutral.

When looking specifically at LGBTQI lawyers, less than half (47 per cent) felt that their employers went beyond tokenism.

While the data didn’t break down what respondents deemed to be tokenistic behaviour, it can be reasonably presumed that such attitudes are borne from seeing engagement and activity that is surface-level only, done as a promotional tool, or lacking in genuine follow-through.

These attitudes are not too dissimilar, arguably, from how lawyers perceive their firms’ approaches to health and wellbeing.

Mr Furness has a slightly different view, however, noting that even visible signs of support from senior leaders, no matter how innocuous, are indicative and symbolic of inclusion.

“Even things like forming a committee, putting materials in an induction pack, seeing your manager with an ally badge on the internet makes a huge difference,” he argues.

“The research tells us that those really quick wins are the simplest and, sometimes, most effective ways that firms can and have made change.”

Such “basic inclusion”, he says, should be seen as encouraging that firm leaders and immediate superiors are, generally speaking, okay with individuals being themselves at work.

But Mr Walker notes that inclusive action on the part of senior management can also work to make a firm’s actions more substantive, rather than appear tokenistic.

“It’s important that the tone is set from the top, and we have the support of our chairman (Fiona Crosbie and managing partner (Richard Spurio). The managing partner chairs our diversity council, where LGBTQI issues and questions for the firm are discussed,” he says.

Where to from here?

Reflecting on the state of affairs, Mr Kirby says that things are “definitely getting better” and have improved significantly over the course of his lifetime.

“When I was growing up, you didn’t have anybody who talked about it, but now, people are talking about it,” he concludes.

“Maybe some people think there’s too much talking about it, but if we talk enough, ultimately we’ll get beyond this and things will get even better. I believe we’re on the right path.”

While there is undoubtedly a long way to go in achieving true, substantive equality of diversity and inclusion, Mr Furness says he is optimistic about the future.

“The conversations I have with senior leaders are always positive given how committed they are to LGBTQI diversity and inclusion, and how much they genuinely want to solve the problem,” he says.

“As long as the senior leaders [are cognizant of] who we are helping, how we are helping them and are committed to making programs work, I think we can have a positive outlook for the LGBTQI community.”

Surveying the profession, Mr Walker said LGBTQI rights had become an important mainstream issue for the legal profession generally.

“Australian firms are taking very positive steps in the right direction to ensure our workplaces are diverse and inclusive,” he proclaims.

“There’s a genuine recognition that not only it is in firms’ business interests to do so, but overall, it makes the work experience, certainly for younger lawyers coming in, a lot more pleasurable and collaborative.”

And when it comes to bringing those falling behind to the table on inclusion and diversity, Mr Kirby reminds us that law is a “special profession”, concerned with big moral questions in society.

“The moral question here is not treating one group in the community as pariahs and abominations, and all the other things we were taught in the past. I think that’s reason enough,” he says.

“We’ve got to make sure that this country is a country of equal justice for all, no exceptions.”

Jerome Doraisamy is the managing editor of professional services (including Lawyers Weekly, HR Leader, Accountants Daily, and Accounting Times). He is also the author of The Wellness Doctrines book series, an admitted solicitor in New South Wales, and a board director of the Minds Count Foundation.

You can email Jerome at: