REVIEW: Growing up during South Africa’s apartheid and forced to endure horrors no one ever should, Lovemore Ndou committed his life to making a name for himself as a world-winning boxing champion and then righting injustices in his capacity as a criminal and family lawyer, all while proving that the impossible is never enough.

On the first page of his first chapter, Lovemore Ndou opens up with a quote from former South African president, Nobel Peace Prize winner, apartheid revolutionary and lifetime hero, Nelson Mandela: “It always seems impossible until it’s done.” The rest of the book follows Mr Ndou’s history as a young child growing up in a harshly segregated country through to becoming a three-time world boxing champion and then a lawyer of his own firm, all the while reinforcing the message that while things may seem impossible at first, there’s greatness at the end.

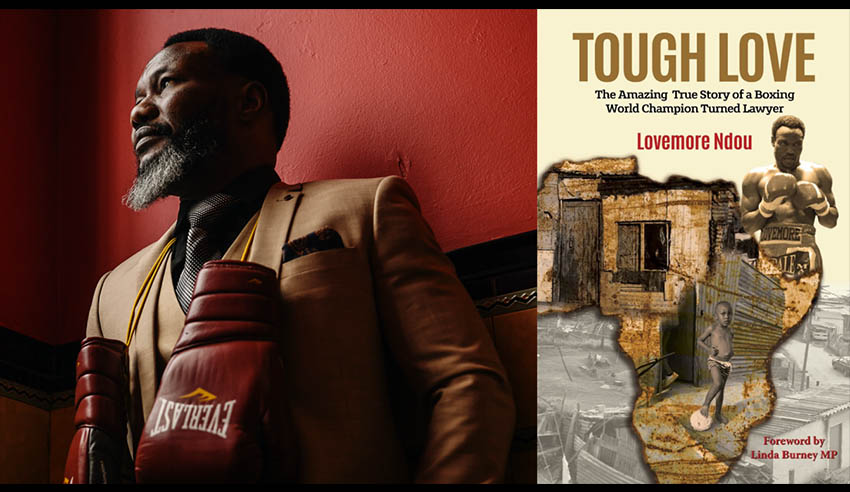

Settled (for now), Mr Ndou spent almost five years penning an autobiography to capture it all and in this conversation with Lawyers Weekly, we talk about Tough Love, the “amazing true story of a boxing world champion turned lawyer” and get into what his legal life looks like now. Just before we sat down, he had been about an hour away from his office with a client and while it was only a reasonable travel distance, I got the feeling that he would have gone much further for those who turn to him.

He said that he wrote the book hoping that one day it would inspire others. Although physical copies have not yet made it to South Africa, he tells me that he has received many thoughts and thank you’s: “One of the most touching things that somebody said to me was that we are very grateful you were able to tell this story. You are like a voice to us. We know exactly what you’re telling because we’ve been through that.”

“I wrote the book hoping that it might one day inspire someone. Just because you don’t have a good start in life doesn’t mean you don’t have a future,” Mr Ndou told me. “If you chase your career and if you work hard, all it takes is some hard work and dedication and sleepless nights and your dream will come true.

“I look back at everything that happened in my life and I see that everything that happened prepared me for today. I started school late but look at me today. I came from a very poor family and look at where I am today. That did not stop me from becoming who I am. I look back and I am sort of grateful that some of those things happened, because they have turned me into a strong, powerful person.”

The transition to lawyer… and a budding political career?

In 2013, Mr Ndou was admitted as a lawyer and started his own criminal and family law firm, Lovemore Lawyers, consisting of a three-room office in Rockdale, Sydney. Family law was inspired by his battle in the Family Court following a broken marriage in which he realised that the rights of children and their ability to have a “meaningful relationship with both parents” mattered above anything else. He also has a story to tell in the criminal law space that he never shies away from telling.

“Funny thing is, I am always sharing my own story with my clients. I’m open to that. Some lawyers will never reveal their own personal life, but I talk to them and I tell them. Sometimes it puts clients at ease, and they understand that it’s not just them going through that, a lot of people are going through that,” Mr Ndou said.

There was one major, defining moment during his teenage years that had really set in stone his dreams to one day make it as a lawyer, even before he had made much of a name for himself. Without spoiling the book’s retelling too much, Mr Ndou had caught the attention of a young, white girl and although he did not return her obvious affections, their very brief appearance together and some whispered rumours in a corner shop in which she worked resulted in Mr Ndou spending some time in prison, wrongfully accused by police of sexually assaulting her.

Mr Ndou showed me a scar on his face, left there by a dog that had been set loose on him while he was locked away in a small cell for a crime he never committed, and explained: “When I was recovering in hospital, I thought to myself, ‘one day, I want to be a lawyer and fight for justice’. If not a lawyer, I want to be a politician.”

While he has settled in the legal profession for now, Mr Ndou has aspirations for his second career choice. In another “four or five years”, he told me that he hopes to have returned to South Africa where he can begin his political campaign.

Armed with those degrees (of which are some of his greatest achievements in life), Mr Ndou gave the first of what I am sure are many promises to come for his hopeful political term: “One thing that I would really want to do, if someday I do end up running that country, I will make sure that education becomes my main priority.”

He said that if you look at South Africa today, it is one of the most developed African countries, but it falls short on the scale when it comes to education, with Zimbabwe and Mozambique ranking higher. He said that once this has been addressed, and once people are educated, there will be better jobs and much less crime.

“I think I can help bring some changes in South Africa. It has been a democratic state for 26 years now, but 26 years later and we still have people living in shacks, using a bucket sanitation system. There’s so much corruption. Somebody needs to step in and stop that. We need great people who can stop that, and we need leaders who are going to listen to people. The current leaders are not listening,” he said.

Lovemore Ndou in his legal offices. Supplied.

He said this is a problem here in Australia, as he watches our government consistently ignore Indigenous people: “All they do is try to give them all these benefits, and you might give them benefits, but you need to listen. Listen to what they want, listen to their problems. I want to try and change that in South Africa.”

Speaking of problems that need to be addressed here in Australia, Mr Ndou wrote about a time he was sitting in a row of chairs dedicated to the legal practitioners waiting for hearings to begin. Although as deserving of that spot as the others, he was singled out by a court officer: “She came up to me and said, ‘no, no, this is reserved for lawyers only’, and ‘oh, are you a lawyer’, but not asking the other lawyers [who were sitting there]. Because I’m Black, I can’t be a lawyer.”

After moments like this, Mr Ndou said he would become a little depressed, but he knew that he had to find a way to deal with it. Much like taking ownership of a judge’s remarks that he was “a bit like a gangster” dressed in his sharp suits, Mr Ndou thought of how he could rise up to it – and thought of reverse psychology: “That is when I went back [to her] and said, ‘Yes, a damn good one’.”

Mr Ndou said he is frequently asked if he thinks Australia is a racist country, but he doesn’t hold any ill thoughts towards it. There are, however, some bad apples and it’s those that stand out from the bunch who demonstrate that apartheid – the same apartheid he grew up around – existed here, halfway across the world.

“The thing I always say, if you stop someone from excelling because of their skin colour, their gender or their sexual orientation, that’s a form of Apartheid. That’s racial discrimination. We all have a bit of Apartheid in us, I believe that,” he said.

“If you look at someone and say, ‘oh, you shouldn’t be doing this job’ just because they are Asian or Black, that’s Apartheid. If you say, ‘oh, I don’t like that person’, just because they are Caucasian, that’s Apartheid. I think that incident [with the court officer] was a form of Apartheid because I wasn’t expected to be a lawyer.”

Despite all of these injustices and slights, Mr Ndou continues to carry with him words spoken to him by his mother on the day of her death: “Never forget to chase your dreams”. He said that every day since that moment, he has carried her words with him and used them to propel him into new opportunities and new careers.

“She knew I had a desire to become a world champion and she knew I could do it and she taught me not to give up and to chase my dream. It was really hard in South Africa, especially during the Apartheid for a Black man to excel through sports or anything else, but she taught me to chase my dreams. She always knew I loved education and she inspired us to be educated so I look back at it and I think that wherever she is now, she is looking down on me and is very happy,” he said.

Where boxing and law meet

For Mr Ndou, to make it as a boxer you need to be cocky, and you need to have an ego strong enough to withstand the pressures of a boxing ring. It’s also just as important in the legal profession. He said that lawyers should never be entering a courtroom doubting themselves, and they should always come prepared. Prepared to fight, prepared to look up at the judge and, more importantly, prepared to lose.

When Mr Ndou would walk away from the ring, he could do so bruised up and hunkered down with pain for a few days. While the physical scars are not a feature of the legal profession, there is another kind of pain that sticks around longer: a bruised ego. Mr Ndou said that in this way and in so many more, his time spent as a famous, world-winning boxing champion prepared him for a career in law.

“When I was a boxer, I was able to speak to people during press conferences and appear on television and speak. I find that really prepared me for the courtroom,” Mr Ndou told me. “The courtroom is a very intimidating place to everyone, but I think I found it a lot easier, because I don’t get intimidated by judges or lawyers. If I can come into a fight and defend myself when someone is trying to lop my head off, what would a judge do to me? They might go off at me, but that doesn’t bother me.”

There are just as many emotions in law as there were in boxing. In his book, he told of one opponent – many years his junior – who picked and taunted him all up until that final match. In the courtroom, lawyers will be hard-pressed to find a temporary colleague who can keep their cool the entire time – and even harder in family law.

While judges are no mental match for him, Mr Ndou did write about a run-in with an opposing lawyer during a particularly tense family law case. The chapter starts off with him explaining the mistaken belief that when he swapped “left hooks for law books”, somehow the fighting would be over. However, he would soon find that frustrations are just as quick to boil over outside of the gloves. Remarkably, after patching things up, that same lawyer is a close friend and confidant.

“Sometimes we just get drawn up and so involved in our client’s cases and, to some extent, we think it’s our case. I just think as lawyers, we need to continue respecting each other. For me, it was a good learning lesson what happened with that lawyer, because it made me realise that as much as I care for my clients and want the best for my clients, I have to remember to always respect other lawyers. My biggest problem [in the beginning] was that I didn’t like losing,” Mr Ndou said.

About midway through the book, Mr Ndou writes about his second coming to Australia and the disastrous turn it takes in the beginning. While I will spare the more exciting details for his own telling, faced with danger, Mr Ndou chants a familiar incantation and begins shadow boxing. He explains the latter as a way to calm his nerves and focus his energy. When I asked how much that small but accustomed ritual plays a part in his current, legal life, I was not left disappointed.

He told me that sometimes, before a big trial, he will pop into the bathrooms and reignite a ritual from long ago: “I will always find, even before fights, each time I shadow box, I am ready for anything. Same thing with the legal profession.”

Lovemore Ndou with nestegg’s Cameron Micallef. Supplied.

Some parts of the profession will come much easier than others, and for Mr Ndou that involves a lot of pro bono work. While winning his world championships is among his favourite boxing memories, winning a successful pro bono case – especially for an Indigenous Australian – is for his legal life: “For me, it’s a way of giving back to the community and also a way of thanking the land owners.”

There are, of course, some parts of the legal profession that lawyers may never be ready for. Near the end of his book, he had one or two quick throwaway sentences in which he spoke about having to defend someone he would have rather seen walk straight into a prison cell. When I asked him about it, he said that case had “bothered me for weeks” and stood out as one that made him rethink his career as a lawyer.

“I took my training in boxing, and that was the way I could deal with it. There are cases like that where sometimes I feel, ‘I have defended the wrong guy’, but it’s just my job. As lawyers, we have got to edge out of it and just apply the law,” he said.

The case in question involved a man who had allegedly sexually assaulted his partner and had threatened her and her family. While he never knew for sure, Mr Ndou suspected that the man and his family had pressured the victim to withdraw and to submit conflicting statements about the assault – if he had known, Mr Ndou said he would not have represented the man, no question about it.

In what speaks to his character as a lawyer and as a person, Mr Ndou said that after he had successfully wrapped up the case in court, the victim approached him outside to tell him he was a good man and that he should not be too hard on himself.

Of course, as lawyers, representing someone who stands against their morals is always bound to be difficult. More so, if they have experience with the crime. Mr Ndou grew up surrounded by sisters, some of whom had been abused at the hands of older men and had come out the other side of it with no justice.

“It really bothers me, and I find it really difficult sometimes dealing with clients who have sexually assaulted someone, because of what my sisters experienced and because they were never given any justice in the end. These are serious offences that should be taken seriously. Luckily, my sisters have had a lot of close family,” he said.

It is these memories – along with so many more, detailed throughout the book – that had to be put down into writing. Mr Ndou said sometimes he would take an eight-or-nine-month break from the book before he could cope with coming back to it. He thanks his brother for finishing it, who always encouraged him to get it done.

“In a way, I’m glad that I did it because it worked out to be something therapeutic. When you feel something, you have got to say something. I’ve found being able to write the book, I was able to relive the memories and face up to the weaknesses. I used to wake up and have nightmares, but I have noticed that as soon as I have stopped writing the book, I don’t have those nightmares that I used to have,” he said.

I was a complete stranger to boxing before I had picked up the book and I only gauged Mr Ndou’s popularity in this space when I mentioned him to a friend and colleague, nestegg’s Cameron Micallef (pictured with Mr Ndou above). None of my boxing naivety stopped me from enjoying the book. If anything, reading about how this part of his life fit in so well with his legal life was made more enjoyable. And bonus: now I’ve got some boxing fun facts for my next sports-fuelled conversation.

While the boxing part of Mr Ndou’s book often overshadows his legal life (it is, after all, found in the sports section of bookstores rather than the biography side next to it), the whole thing was well worth the read. Readers will come away with a real, heart-wrenching understanding of what it is like to live through the apartheid and how those dreadful experiences created a man leading the charge in his own firm. Plus, if his aspirations are anything to go by, it’s a good look into a future politician.

As for final messages, Mr Ndou echoed the words of Mr Mandela: “Believe in yourself. This is a story that shows if you believe in yourself, the world is yours.”