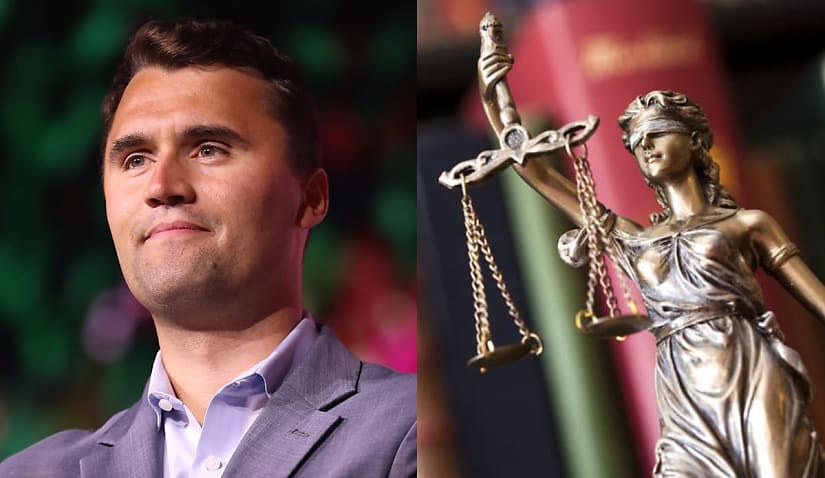

The assassination of conservative campaigner, activist, and podcaster Charlie Kirk at a Utah-based university campus recently has ignited a firestorm in the United States – a nation whose social cohesion is already hanging on by a thread. In the aftermath of that killing, there has been a torrent of activity to “cancel” those expressing unsavoury, or even politically unaligned, commentary online. Australian employees, like lawyers, may not be immune from this.

Cancel culture

Last week, US-based publications reported that an insurance litigator at BigLaw firm Perkins Coie was fired, effective immediately, for a social media post that called Kirk “one of America’s leading spreaders of hatred, misinformation, and intolerance”.

The post went on to say that “no one in this country should be murdered for their political speech”, but the post caused online outrage, and Perkins Coie terminated the lawyer, saying in a reported statement that “these comments do not reflect the views of our firm, and the individual’s conduct in posting them fell far short of the expectations we have of everyone who works here”.

The firing is far from the only instance of a worker losing their job since Kirk’s killing.

As reported by Lawyers Weekly’s sister brand, Cyber Daily, a website, called Cancel the Hate, was created to “out” professionals and to “ensure that individuals in positions of power cannot hide hateful words or actions from public scrutiny”. The site was recently taken down over an alleged leak of user data, but until then, it was actively recruiting users to share details of professionals who had been publicly critical of Kirk.

“CancelTheHate.com exists to shine a light on hateful behaviour that poses a risk to communities particularly when it comes from people whose positions carry power and influence,” the site said.

Efforts to “cancel” workers have also spread Down Under – as recently reported by ABC, South Australia Police are investigating the social media posts of one of its staff, for allegedly celebrating Kirk’s killing online. “They are now subject to an investigation under the Police Complaints Disciplinary Act,” a police spokesperson said.

The calling out of employees to their employers could well be viewed as a matter for private entities to manage. However, while serving as a guest host of Kirk’s podcast, US Vice President JD Vance said those who celebrate the assassination should be held accountable.

“Call them out, and hell, call their employer,” Vance said.

Speaking on The Lawyers Weekly Show earlier this year, Maurice Blackburn principal Josh Bornstein reflected on “corporate cancel culture”, noting that the “increasingly oppressive” control that businesses have over employee freedoms is undemocratic and that we are well into what he sees as a “second Gilded Age”.

The objectively horrific nature of Kirk’s death, and the resulting discourse, raises fresh questions about the extent to which workers can express personal views in public forums, and how much freedom employers will give their workers – either proactively or reactively.

In today’s volatile political climate, Hall & Wilcox partner Fay Calderone told Lawyers Weekly, social media has “become both a platform for free expression and a battleground for public accountability”, with a growing trend of calling for employees to be terminated over controversial views.

Various highly emotive incidents in the world are testing the boundaries of workplace expression, and employer discretion has revealed an unpredictable intersection between political discourse, employment law, and social media.

Calls for individuals to be fired over online commentary, Pinsent Masons partner Aaron Goonrey said in support, “reflect a growing trend of moral outrage influencing workplace decisions”.

“Various highly emotive incidents in the world are testing the boundaries of workplace expression, and employer discretion has revealed an unpredictable intersection between political discourse, employment law, and social media,” he said.

The killing of Charlie Kirk, Swaab partner Michael Byrnes added, has resulted in visceral, emotionally driven responses from across the political spectrum.

“As the culture wars play out online, targeting the employment of an ideological adversary has become a strategy to seek to score points and stifle expression,” he said.

However, he added, just because a member of the public aggrieved by an employee’s post complains to an employer “does not mean that employer either can or should take any action in relation to it, even if the employer disagrees with the content of the post”.

Legal precedent

To understand how to approach such a delicate sociopolitical age, made infinitely worse by the proliferation of social media and the abovementioned oppressive corporate cancel culture, one first needs to appreciate how the courts are interpreting such matters.

Calderone explained that the overarching principle, established in the leading authority of Rose v Telstra Corporation Limited, from the Australian Industrial Relations Commission, highlighted that an employer’s ability to terminate an employee for out-of-hours misconduct is limited to circumstances where there is a “sufficient connection” to the employment relationship.

It is not sufficient, she advised, for the employer to “simply assert that the conduct will in some way affect the employer’s reputation or compromise the employee’s capacity to perform his or her duties, there needs to be evidentiary material upon which a firm finding may be made” (as per the Fair Work Commission matter of Wakim v Bluestar Global Logistics). Moreover, she went on, personal out-of-hours conduct must have a clear and serious impact on the workplace before it warrants dismissal (per the FWC proceedings in Starr v Department of Human Services).

However, Calderone continued, a decision to discipline or terminate an employee cannot breach state and federal discrimination laws or the Fair Work Act, which applies to employees and contractors of national system employers, and prohibits adverse action on discriminatory grounds or based on protected attributes.

“Specifically, a decision to take disciplinary action or terminate employment or engagement cannot be made based on prohibited grounds under and the Fair Work Act, which prohibits adverse action being taken against workers because they have a certain feature or attribute,” she said, including but not limited to race, sexual orientation, breastfeeding, age, disability, marital status, religion, or political opinion.

“If adverse action was taken for reasons that include protected attributes, the onus is on the employer to prove the termination of employment was not for reasons that included any such attributes. They need not be the sole or dominant reason, but rather an operative reason in the mind of the relevant decision-maker.”

More recently, Calderone pointed out, in the “significant” case of Lattouf v Australian Broadcasting Corporation, the Federal Court confirmed that adverse action was taken against Lattouf based on her political opinion, in contravention of the Fair Work Act, for a social media repost she made out of hours.

“This determination sent a clear message to employers that even in turbulent times, employers cannot discipline employees for their personal political beliefs,” she said.

Employer best practice

In addressing any issues or complaints arising from a Charlie Kirk-related social media post, Byrnes detailed, employers “should avoid emotion”, and go back to first principles relating to out-of-hours personal conduct by employees.

One key question to consider, he said, is whether the post is connected to employment.

“If the post is on a personal social media account that makes no reference (either directly or indirectly) to the employer, then the appropriate response might be that it is a private matter relating to the employee and the issue should be taken up with them directly. If the post is on an account that refers to the employer (such as LinkedIn), then that might provide a sufficient nexus with employment for the employer to consider taking action, if the post is potentially detriment to its interests,” he said.

“While consideration should be given to the social media policy of the employer, be aware that some such policies can sometimes be poorly drafted, going beyond an appropriate and enforceable management prerogative in regulating posts on an employee’s personal social media account.”

The substance of any post in question, Byrnes continued, also needs to be carefully and objectively assessed.

“In the polarised discourse that has followed Charlie Kirk’s assassination, some commentators have put all of those who have, in their view, failed to honour the memory of Kirk in a sufficiently deferential way, into the same category,” he said.

“In determining whether a post by an employee breaches any obligations, the language and context of the post need to be very carefully considered. A post expressing unbridled jubilation at the death is distinguishable from a post that merely repeats and critiques views expressed by Kirk in his lifetime.”

“While many subscribe to the aphorism ‘don’t speak ill of the dead’, particularly those who have recently departed, that is going to be an overly simplistic and moralistic approach for an employer to take in determining whether a post should lead to disciplinary action.”

In any disciplinary matter, Byrnes advised, employers need to “avoid playing moral arbiter”, and look at the matter clinically by reference to damage to their interests.

Looking ahead, Calderone advised, employers are in the challenging position of ensuring their responses to such instances align with core organisational values, preserve reputation, social cohesion, and trust, while also balancing compliance with onerous laws.

“Public statements that conflict with a business’s purpose or risk damaging relationships with clients, regulators or stakeholders may justify a proportionate response,” she said.

Employee duties

For practitioners, both in-house and in private practice, Calderone said, the bar is higher.

“As trusted advisers bound by professional ethics, they must exercise discretion online, avoid inflammatory commentary and ensure personal expression does not compromise professional integrity,” she said.

Goonrey backed this, noting that for individuals, the current environment demands heightened awareness. “Not just of what they or their employees post, but how their words may be interpreted in politically charged climates,” he said.

As social media continues to serve “both as a megaphone and a minefield”, he mused, legal professionals must tread carefully, balancing personal expression with professional responsibility.

“It is also a timely reminder that having an active digital footprint means the possibility of it being seen by employers or clients,” he said.

“Employees should review access to their personal social media channels not associated with their professional persona to make sure they are taking the necessary steps to protect their professional reputation.”

This, of course, “can create tension between building a professional reputation and being a concerned citizen, and accordingly can have an impact on free speech”, he added.

Reflections

While employers have legitimate interests in protecting their reputation and workplace harmony, Goonrey mused, the rush to dismiss employees for personal views expressed online “risks undermining principles of proportionality and due process”.

This would, he said, certainly be the case under Australian employment law.

To this end, Calderone said in support, and “in an age where a single post can spark outrage, lead to reputational damage and significant legal risks and result in termination of employment (rightly or wrongly)”, both employers and employees must “tread carefully” to balance freedom of expression with legal and ethical obligations.

This extends, of course, to how one is perceived as a lawyer and wants to be perceived.

Ultimately, Byrnes concluded, members of the legal profession are expected by their clients to provide and demonstrate sound judgement.

While certain topics and events can engender strong emotions and reactions – most recently, as witnessed with Kirk’s assassination – and while lawyers should be entitled to express robust opinions on such matters (“and are a cohort likely to hold such opinions”), doing so in “an extreme, reckless or intemperate way” can not only potentially jeopardise employment, he said, but may also lead clients and colleagues to question their professional judgement as a lawyer.

Jerome Doraisamy is the managing editor of professional services (including Lawyers Weekly, HR Leader, Accountants Daily, and Accounting Times). He is also the author of The Wellness Doctrines book series, an admitted solicitor in New South Wales, and a board director of the Minds Count Foundation.

You can email Jerome at: