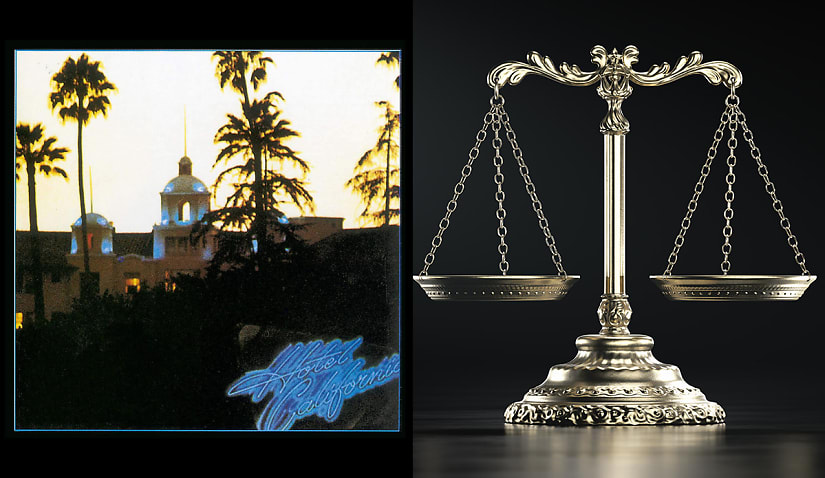

The “Hotel California lawyer” isn’t inevitable and shouldn’t be accepted as the cost of doing business in law, writes Rebecca Ward, MBA.

Album cover: Asylum Records

When disengagement becomes the default

The legal profession prides itself on resilience, intellect, and unwavering commitment. Lawyers are trained to overcome adversity, work punishing hours, and strive for perfection. But what happens when the very drive that propels legal professionals to success becomes the force that drains them?

Not all lawyers experiencing burnout walk away. Many stay – physically present but emotionally absent, adrift in a profession that once inspired them but now feels like a relentless obligation. They are not on sick leave or planning to resign. They show up, bill hours, and complete tasks, but they’ve stopped caring. These are the lawyers who’ve “checked out”.

While absenteeism describes being physically absent from the workplace, and presenteeism refers to working while unwell or mentally depleted, disengagement is something more enduring. It is the slow erosion of purpose and motivation, where the lawyer is no longer unwell, just disconnected. And unlike “quiet quitting” or “silent resignation”, these lawyers aren’t secretly planning their exit. They’ve resigned themselves to staying.

In short, they’ve checked out – but never left.

Welcome to the legal profession’s own Hotel California.

The anatomy of legal disengagement

Disengagement in law doesn’t happen overnight. It is often the cumulative result of long-term overwork, emotional exhaustion, and an eroding sense of meaning. These lawyers continue billing, advising, and litigating – but with a growing sense of detachment.

Common signs of a lawyer who has checked out include:

Left unaddressed, this quiet disengagement can deepen into chronic presenteeism, where lawyers stay in the building and on the payroll but no longer mentally or emotionally show up.

Why lawyers stay after they’ve checked out

Disengagement is common across many professions, but in law, unique cultural and structural factors make checking out more likely than leaving altogether.

1. The sunk-cost fallacy

Lawyers invest years (often decades) into building their careers. They accrue degrees, debts, professional titles, and social identity. Leaving can feel like discarding all that hard-earned capital.

“I’ve put too much into this to quit now.”

“What else would I do after all these years?”

Rather than pivot, many lawyers simply settle in – even if their dissatisfaction is palpable.

2. Lack of visible alternatives

Legal career pathways are often linear and rigid: associate to senior associate, senior associate to partner. Moving sideways – to in-house roles, academia, policy, or even a career break – can feel stigmatised or like a step backward.

“Do I really want silk? Or am I just chasing the next milestone?”

“If I step away from partnership, does that mean I’ve failed?”

3. Golden handcuffs

The financial rewards of prestigious firms often come with personal costs. High salaries, mortgages, and family obligations make the idea of leaving feel impossible.

“I’d leave, but I can’t afford to.”

“I should be grateful – why do I feel this way?”

4. Law as identity

For many lawyers, the profession isn’t just a job – it’s who they are. Their intellect, competence, and sense of worth are tightly bound to their role.

“If I’m not a lawyer, who am I?”

“I can’t walk away from everything I’ve built.”

Re-engagement (before it’s too late)

The good news is that disengagement doesn’t have to be permanent. Lawyers and firms can take meaningful steps to prevent burnout from calcifying into emotional disconnection.

For lawyers:

For law firms:

Unchecked disengagement has ripple effects. It affects wellbeing, team morale, client relationships, and long-term professional sustainability.

Lawyers deserve more than survival mode

The “Hotel California lawyer” isn’t inevitable and shouldn’t be accepted as the cost of doing business in law. Disengagement may be quiet, but its impact is profound. Lawyers deserve careers that are not only financially viable but personally meaningful and emotionally sustainable.

Sometimes, re-engagement is possible. Sometimes, stepping away is the healthiest decision. Either way, the goal must be the same: not just to retain talent but also to restore purpose. Because you can check out anytime you like, but if no one helps you find the exit, you may never leave.

Rebecca Ward is an MBA-qualified management consultant with a focus on mental health. She is the managing director of Barrister’s Health, which supports the legal profession through management consulting and psychotherapy. Barristers’ Health was founded in memory of her brother, Steven Ward, LLB.